Curtain raiser

2023 Conferences of the Parties to the Basel, Rotterdam, and Stockholm Conventions (BRS COPs)

The Rotterdam Convention on the Prior Informed Consent Procedure for Certain Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides in International Trade is a global treaty between 165 countries that provides early warning to countries about a broad range of hazardous chemicals that are traded internationally. The information shared under the Convention, including whether a hazardous chemical is banned or severely restricted in other countries, enables governments to assess the risks posed by these chemicals to human health and the environment, and to make informed decisions on their import. It is one of the Basel, Rotterdam, and Stockholm Conventions—a triad of agreements that together tackle the life cycle of global chemicals and waste management.

Why was the Rotterdam Convention developed?

Chemicals are a vital part of people’s daily lives. They are used in the construction industry, in electronics, to make different sorts of plastics, in consumer care products, and in agriculture, where they are used to make fertilizers and pesticides. In fact, the chemical industry represents one of the largest sectors of the global economy. The dramatic growth in chemicals production and trade, especially during the 1960s and 1970s, raised both public and official concern about the risks posed by hazardous chemicals and pesticides.

In many developing countries, government officials did not have the assessment capabilities, regulatory regimes, or infrastructure to effectively manage the risks posed by the import and use of hazardous chemicals. This increased the possibility the misuse or mishandling of hazardous chemicals could harm human health and the environment.

This concern prompted the development of the International Code of Conduct for the Distribution and Use of Pesticides by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the London Guidelines for the Exchange of Information on Chemicals in International Trade by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). In 1989, policymakers amended both instruments to include a voluntary prior informed consent (PIC) procedure to help countries make informed decisions on the import of chemicals banned or severely restricted elsewhere.

When the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (Earth Summit) convened in Rio de Janeiro in June 1992, delegates recognized the use of chemicals is essential to meet global social and economic goals, but also acknowledged a great deal remains to be done to ensure the sound management of chemicals. Chapter 19 of Agenda 21, the programme of action adopted at the Earth Summit, contains an international strategy for action on chemical safety. Paragraph 19.38(b) calls on states to achieve by the year 2000 the full participation in and implementation of the PIC procedure—including possible mandatory applications of the voluntary procedures contained in the amended London Guidelines and the International Code of Conduct.

This led both the UNEP Governing Council and the FAO Council to agree to jointly convene an intergovernmental negotiating committee with a mandate to prepare an international legally binding instrument for the application of the PIC procedure. Negotiations began in 1996 and the Rotterdam Convention was adopted in September 1998.

How does the Rotterdam Convention work?

The Rotterdam Convention, which entered into force in February 2004, creates legally binding obligations for the implementation of the PIC procedure. The objectives of the Convention are to promote shared responsibility and cooperative efforts among parties in the international trade of certain hazardous chemicals to protect human health and the environment from potential harm, and to contribute to the environmentally sound use of those hazardous chemicals by: facilitating information exchange about their characteristics; providing for a national decision-making process on their import and export; and disseminating these decisions to parties.

The Convention establishes a prior informed consent (PIC) procedure to ensure restricted hazardous chemicals are not exported to countries that do not wish to receive them. The aim is to promote a shared responsibility between exporting and importing countries to protect human health and the environment from the harmful effects of certain hazardous chemicals. The PIC procedure does not ban or restrict any chemicals, nor does it mean that any individual country must automatically prohibit their import. It simply raises awareness of what chemicals are deemed to be hazardous. The PIC procedure applies to chemicals listed in Annex III of the Rotterdam Convention, which includes pesticides, industrial chemicals, and severely hazardous pesticide formulations (SHPFs).

The Convention established a Chemical Review Committee (CRC), which reviews notifications submitted from parties about chemicals that may need to be covered by the PIC procedure. The CRC reviews notifications of final regulatory action (FRA) against the criteria set out by the Convention in Annex II (for chemicals) and IV (for SHPFs) and make recommendations to the Conference of the Parties (COP) for listing such chemicals in Annex III.

There are two ways to trigger the addition of new chemicals to Annex III. For pesticides and industrial chemicals, all parties must notify the Secretariat of any rules they have adopted domestically to ban or severely restrict a chemical for environmental or health reasons. When the Secretariat receives two notifications of FRA from two different PIC regions (Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, Near East, North America, and Southwest Pacific) that meet the criteria established in Annex I to the Convention (which describes properties, identification, and uses of the chemical and information on the regulatory action), it forwards the notifications to the review committee. The committee then screens the notifications according to the criteria contained in Annex II. If the CRC finds the criteria are met, it recommends listing the chemical in Annex III and prepares a decision guidance document for consideration by the COP.

Any party that is a developing country or country with an economy in transition can propose a SHPF for listing. The CRC screens these against the criteria in Annex IV, which specify the documentation required from a proposing party, the information to be collected by the Secretariat, and the criteria for listing the SHPF.

To date there are a total of 54 chemicals listed in Annex III, including 35 pesticides (three are SHPFs), 18 industrial chemicals, and one chemical in both the pesticide and the industrial chemical categories. These chemicals are subject to the PIC procedure and each party is supposed to ensure a chemical listed in Annex III is not exported from its territory to any importing party that has not provided explicit consent to the import.

Is there a Difference between a Listing and a Ban?

When a chemical is listed in Annex III to the convention, it does not mean the chemical is banned. Nor does it mean the chemical cannot be exported. The listing initiates an information-sharing process and requires the PIC of importing countries. However, one of the challenges the Rotterdam Convention faces is that many parties interpret a “listing” as constituting a ban, which poses an economic threat to producer countries and industries producing the chemical in question. Even though it is not a ban, some believe a listing is the first step toward an eventual ban on the chemical. Thus, when a chemical comes before the CRC or the COP, some producer countries and industry representatives lobby against the listing of the chemical. As a result, six chemicals—including chrysotile asbestos and the pesticides acetochlor, fenthion ultra-low volume formulations, paraquat dichloride formulations, and carbosulfan—have been on the COP agenda for years but have not been able to get the necessary consensus to be listed in Annex III.

The case of the pesticide acetochlor illustrates this problem. Opponents of listing the chemical argued at COP10 in 2022 that the pesticide is in use in their countries and listing acetochlor would raise the price of agricultural production; listing is tantamount to a ban; and reduced availability of effective crop protection tools like acetochlor is a risk to the global trade of low-cost food.

Proponents of listing emphasized that acetochlor is harmful to human health, and that listing facilitates information exchange between countries and does not constitute a ban. The debates on the other pesticides in question followed a similar pattern.

What is the Problem with Chrysotile Asbestos?

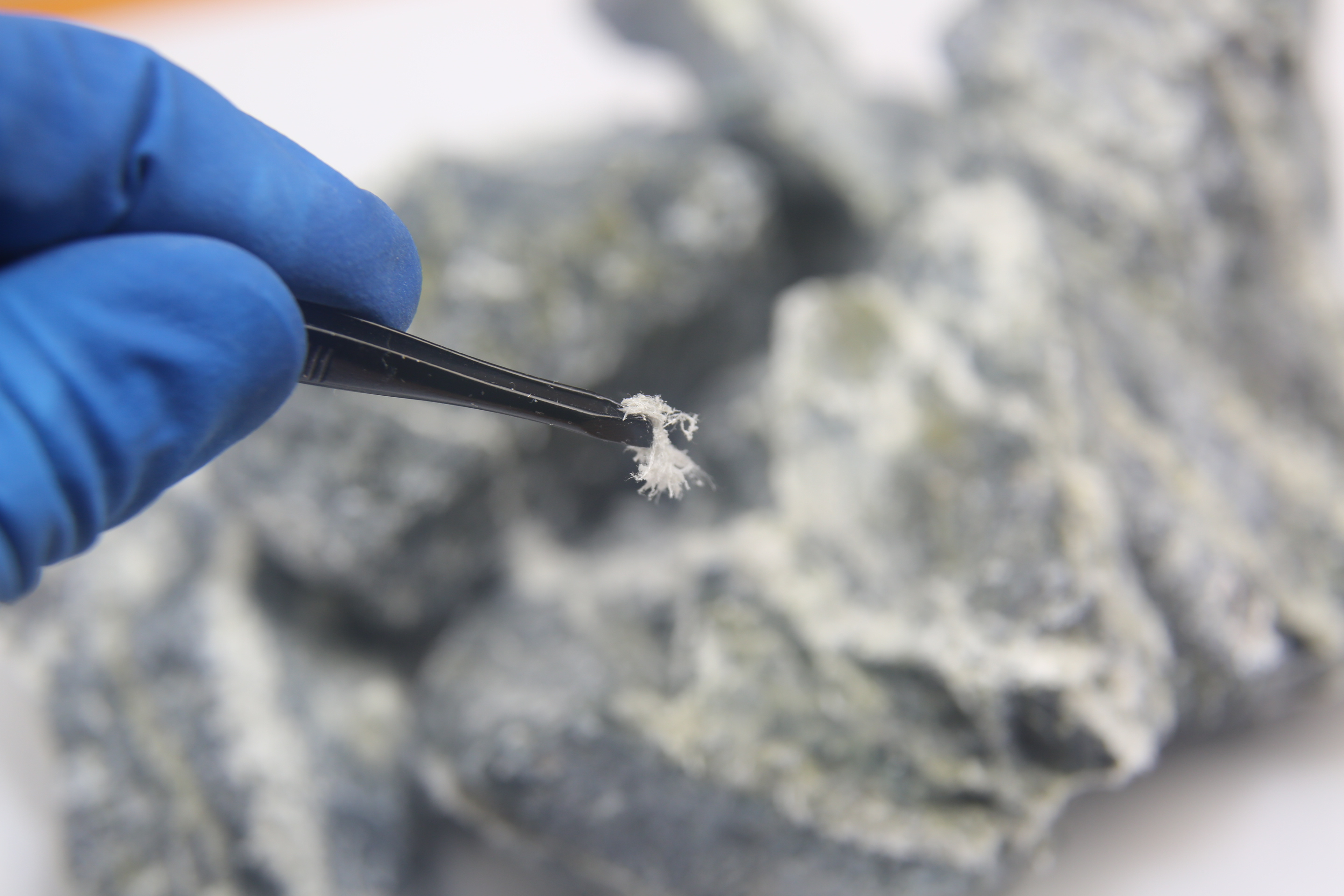

Since 2006, the Rotterdam Convention has been unable to reach agreement on the listing of chrysotile asbestos. All forms of asbestos are listed under the Rotterdam Convention with the exception of chrysotile asbestos, also known as white asbestos. It is used in roofing materials, textiles and cement as well as gaskets, clutches, brake pads and other automotive parts.

When asbestos fibers are breathed in, they can get trapped in the lungs and over time, these fibers can cause scarring and inflammation, which can affect breathing and lead to serious health problems. Each year, an estimated 255,000 people worldwide die from asbestos-related cancers and respiratory disease, according to the American Public Health Association. Asbestos causes mesothelioma and cancer of the lung, larynx, and ovary. It is also associated with cancer of the pharynx, stomach cancer, and colorectal cancer. There is no safe level of exposure to asbestos, and nearly 70 countries have banned it.

In 2006, the CRC recommended the COP list chrysotile asbestos under the PIC procedure. It has been considered at every COP since without an agreement on listing the chemical in Annex III. For example, at COP10 in 2022, parties that still use chrysotile asbestos, including such countries as Kazakhstan, the Russian Federation, Zimbabwe, India and Pakistan, and the International Alliance of Trade Union Organizations “Chrysotile” opposed listing, citing inconclusive scientific evidence, and noting that chrysotile asbestos is a cost-effective option in the construction industry in developing countries and economies in transition. Numerous other developed and developing countries, non-governmental organizations and other trade union groups, supported listing, with many noting national bans of chrysotile asbestos and stating that a listing would protect countries’ right to know about the import of hazardous chemicals and provide the necessary information to help protect workers and communities. Both the World Health Organization and the International Labour Organization have supported listing.

Since the COP has to approve listing chemicals in Annex III by consensus, these divergent opinions have led to a stalemate for over 17 years. One observer has gone so far as to say this stalemate shows that “the Rotterdam Convention is broken.” Concerned that the financial interests of a few powerful governments and the asbestos industry are threatening the lives of millions, he asked “How many hundreds of thousands of people must die from asbestos-related diseases before the parties to the Rotterdam Convention change this?”

Can the Rotterdam Convention be reformed?

The stalemate on the listing of chemicals has led to calls for reform. During COP10, some delegates hinted that changing the decision-making rules to allow voting might be the only way forward. Yet at the same time, they acknowledge resistance to such a move would almost certainly be enormous. But fears about the future of the Convention might motivate parties to take bold steps to break the pattern of deadlock.

For many developing countries, this Convention is the only way to track hazardous chemicals entering their borders and increasing threats to human health and the environment. It is important to communicate these threats to a wider audience, so the public is aware of the threats these chemicals pose to human health and the environment. While it may not be necessary to list hazardous chemicals like chrysotile asbestos under the Rotterdam Convention to protect people and the environment, it may be necessary to ensure the future effectiveness of the Convention itself.