News * Abou us * the ENB team * DONATE * Activities * Search * IISD RS home * IISD.org * RSS * What is RSS? * Links |

|

MEA Bulletin Guest Article

Tuesday,

15 May 2007 CLIMATE POLICY AND HIGHER EDUCATION: STRENGTHENING UNIVERSITY CONTRIBUTIONS IN VULNERABLE COUNTRIES By Mary Jo Larson, Ph.D., Consulting Practice in Leadership, Peace Building and Sustainable Development, Senior Fellow, University for Peace Full Article In February 2007, the University for Peace organized the Climate Change and Vulnerability Conference1 in the Peace Palace of The Hague. Participants included policy makers, technical experts, scholars and community leaders from over 30 countries. The Netherlands, a low-lying country where flood defense and precautionary measures are the highest in the world, offered a fitting location for the exchange of ideas on climate adaptation and the role of higher education. During opening remarks, Dutch diplomat Jan Pronk recognized that both mitigation and adaptation are required and challenged the participants to cooperate internationally and be consistent—and equitable—in their commitments. He highlighted progress made through multilateral agreements, including the Kyoto Protocol, yet expressed frustration with the lack of concrete and creative action. Ambassador Enele Sopoaga of Tuvalu warned that there is an urgent need for adaptation. “Small Islanders are potential environmental refugees,” he stated. “What we need now is the implementation of concrete projects on the ground. Unless adaptation measures are implemented, sustainable development is severely compromised.” These comments set the stage for the Conference’s deliberations. Background The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 4th Assessment Report concludes that it is 90% certain that human-generated greenhouse gases are heating the planet at a dangerous rate, and the evidence is “unequivocal.” Coastal and Small Island nations are among the most vulnerable to climate warming. Hazards include rising sea levels, flooding, coastal erosion, loss of biodiversity, drought and extreme weather events. The poor, though not responsible, are the most vulnerable and least able to adapt. The concerns and priorities of vulnerable coastal and Small Island states are clearly acknowledged in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, multilateral agreements such as the Mauritius Strategy, regional policy frameworks, national policy instruments and related plans. At this stage, there is growing frustration that international climate change “rhetoric” is not leading to concrete action at national and community levels. Mainstreaming Adaptation How best to address climate adaptation? Small groups discussed coastal management, water and health, disaster risk management and cities of the future. Recommendations for mainstreaming included:

Climate-related training in forecasting and planning is offered by non-government organizations and regional institutions. At government levels, training is designed to improve knowledge, information sharing, negotiations skills, and the development of adaptation plans. At community levels, training seeks to manage risks by demystifying climate information, making it locally relevant. All projects require longer-term commitments and the dissemination of case studies and effective practices. For that, we considered the role and potential contributions of higher education. Role of Higher Education

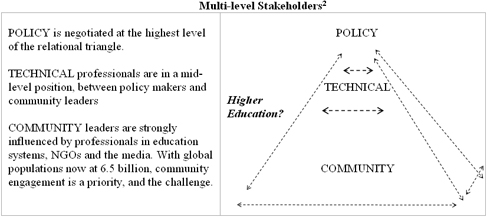

Universities are “knowledge

hubs” with influence at the

policy and community levels.

Higher education and other

technical professionals are

strategically positioned between

policy makers and community

leaders. With access to both,

they are potential mediators for

the transformation of society’s

infrastructures. The pyramid

(below) illustrates the dynamics

of these multi-level relations. How do universities contribute to the implementation of adaptation policies? Many programs now infuse climate-related topics or activities into existing courses. This raises general awareness and is the easiest approach. In some cases, new interdisciplinary courses and programs have been developed. This integration requires greater commitments of time and resources. A number of examples were presented during the Conference. The University of the South Pacific, which is jointly owned by the governments of twelve island countries, for example, has a Centre for Excellence for sustainable development. Masters of Science courses integrate climate change into environmental and social development, and students are required to engage in participatory community activities to provide practical, hands-on learning. At Wageningen University, in The Netherlands, the Environmental Systems Analysis Group is developing global research and communication technologies. “Natures Calendar” is an Internet program used to educate the public about the timing of life cycle events and the ecological impacts of climate change. Increasing this knowledge increases support for climate mitigation and adaptation. Ibaraki University, in Japan, has developed an interdisciplinary course for professionals called “Adaptation Science.” Experiential learning is used to integrate climate sciences, policy negotiations, green options, and adaptation measures. Dr. John Hay described a case: Roads are usually built away from the coast, but Japan does the opposite; it builds roads on the coast. If roads are built inland, it will lead to destruction of shrines and temples. What are the costs of keeping roads on the coast? To answer this question, engineers and other professionals develop detailed plans, considering climate, storm surges, coastal erosion, and flooding. UNESCO’s Co-operative Programme on Water and Climate (UNESCO-IHE), with headquarters in The Netherlands, trains professionals from developing countries. Courses cover all aspects of climate change (cause-effect chain, adaptation, institutions), and they are offered in cooperation with international institutions. The University Consortium of Small Island States (UCSIS) enhances the capacity of graduate education institutions by facilitating implementation of the Barbados Programme of Action. To design curricula for climate leadership, Dr. Fazal Ali noted that “curriculum as thinking” transforms teachers, learners, texts and content. It is based on a capability approach and produces people who can go beyond the information given. In contrast, competency-based curriculum serves to transmit the certain and the fixed. The University for Peace, in Costa Rica, is authorized by the United Nations to grant Master’s and Doctoral degrees in peace and conflict studies. The Environmental Security Program offers an interdisciplinary course on climate change, and conflict management courses infuse climate issues through the analysis of multilateral negotiations. To disseminate curricula, the university facilitates partnerships with other institutions. Challenges and Recommendations Universities are addressing climate issues, but there is a need for more cooperation as well as to address other challenges. Departments and degree programs within them remain insular. Chairs and professors may not have the interest or capabilities to foster leadership, innovative thinking, and local adaptation. In some cases, resistance is related to quality assurance, which affects accreditation. In other cases, there is a lack of institutional support or funding predictability. In developing nations, the lack of resources is a major barrier, and these nations request that curricula and other resources be available online. Participants at the meeting identified a number of ways to strengthen the contributions and impact of higher education:

To conclude, there is urgent need for action, and it is essential to cooperate more fully in addressing climate change. Long-term capacity building is needed at all levels: policy, technical and community. The challenge for higher education is to cultivate the commitment and flexibility to work more closely with partner education, training and research institutions. Ultimately, there is no sustainable development without dynamic, multi-level cooperation. 1 For conference details, contact Mary Jo Larson at maryjolarson@mac.com or visit http://www.upeace.org/climate or http://www.allianceforupeace.nl/ or, in the near future, http://www.myucsis.com/ 2 Expert consultations on International Environmental Governance, 28-29 May 2001, Cambridge, UK (see http://enb.iisd.org/crs/ieg/ for more information). |