Summary

The following events were covered by IISD Reporting Services on Tuesday, 13 December 2016:

- Teaching Biodiversity Mainstreaming to all Stakeholders

- Peace and Biodiversity Dialogue Initiative: Transboundary Conservation for Biodiversity and Peace

- Assessing Equity in Protected Area Conservation

- Synthetic Biology and Synbiodiversity: How New Biotechnologies are Raising New Philosophical Questions for Biodiversity Conservation

- Biodiversity Governance – Identifying Knowledge Gaps and Needed Research Activities

- Sharks, Parks and Whales: Non-Extractive Uses of Marine Biodiversity Need Protection!

IISD Reporting Services, through its ENBOTS Meeting Coverage, is providing daily web coverage of selected side-events from the UN Biodiversity Conference.

Photos by IISD/ENB | Diego Noguera

For photo reprint permissions, please follow instructions at our Attribution Regulations for Meeting Photo Usage Page.

Teaching Biodiversity Mainstreaming to all Stakeholders

Presented by the Instituto Mora, Mexico, and the University of Trento, Italy

This event, moderated by Simone Lucatello, Instituto Mora, Mexico, discussed new tools for theoretical and practical training on integrated approaches to biodiversity mainstreaming. Discussants showed how these tools support implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Rio Conventions with parallel strategic agendas.

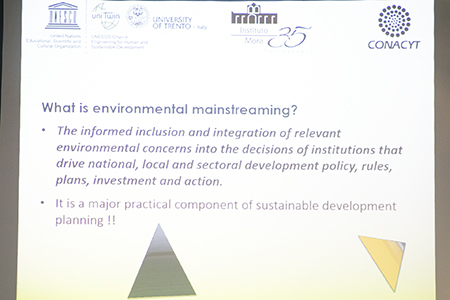

Lucatello defined environmental mainstreaming as the inclusion and integration of relevant environmental concerns, particularly conservation and sustainable use, in plans, programmes and sectoral and intersectoral policies at all levels of decision making.

Hesiquio Benítez Díaz, National Commission for the Knowledge and Use of Biodiversity (CONABIO), said mainstreaming requires capacity building and integrated approaches in order to break down barriers and silos between institutions and agencies. He said this approach was necessary in order to build a common vision of all stakeholders involved in organizing the thirteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD COP 13) in Mexico.

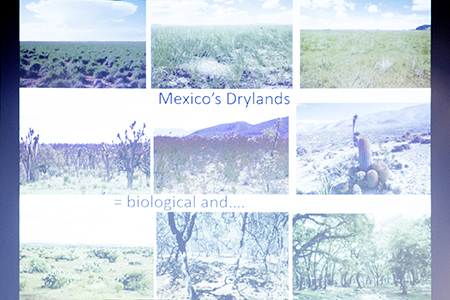

Elisabeth Huber-Sannwald, Instituto Potosino de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica, A. C. (IPICYT), Italy, presented a case study on mainstreaming biodiversity and the SDGs in drylands. She noted the need for new approaches to understand biophysical and socio-economic factors of desertification in order to focus more on the cause rather than the effects. In this regard, she stressed the need for a shift in focus from ecosystems to socioecological systems, and for the long-term monitoring of trends from identified baselines.

Massimo Zortea, UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Chair, University of Trento, outlined six steps for incorporating environmental mainstreaming into education and training: awareness raising; personal and collective willingness raising; capacity development; participation; actions or practice; and evaluation. He noted that the handbook for environmental mainstreaming for environmental studies contains case studies, best practices and vast references necessary for training.

In discussions, participants noted that: mainstreaming of the production and environment sector is required; capacity building should be demand-driven; and there is need for an experience-sharing network on best practices.

(L-R): Hesiquio Benítez Díaz, CONABIO; Elisabeth Huber-Sannwald, IPICYT; Simone Lucatello, Instituto Mora, Mexico; and Massimo Zortea, UNESCO Chair, University of Trento

A slide from the presentation of Elisabeth Huber-Sannwald

Elisabeth Huber-Sannwald, IPICYT, Italy, said in order to have more integration of knowledge systems, transdisciplinary approaches are required.

A slide from the presentation of Simone Lucatello

Simone Lucatello, Instituto Mora, Mexico, introduced a new handbook for environmental mainstreaming for undergraduate, postgraduate and professional levels, developed by Instituto Mora and University of Trento.

Massimo Zortea, UNESCO Chair, University of Trento, said integrating higher education means including environmental mainstreaming into vocational programs, with multi- and inter-disciplinary contents.

Hesiquio Benítez Díaz, CONABIO, said the main focus of the CBD COP 13 was to support implementation of the Strategic Plan 2011-2020 and the Aichi Biodiversity Targets through mainstreaming, with emphasis on the agriculture, forestry, fisheries and tourism sectors.

Contact:

- Simone Lucatello

| slucatello@mora.edu.mx - Massimo Zortea

| massimo.zortea@unitn.it

More Information:

Peace and Biodiversity Dialogue Initiative: Transboundary Conservation for Biodiversity and Peace

Presented by the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)

This event, moderated by Sarat Babu Gidda, CBD Secretariat, officially launched the Peace and Biodiversity Dialogue Initiative (PBDI) website. Gidda noted the need to showcase the practicality of peace and biodiversity dialogues, lauding the Republic of Korea for furthering this cause. He described peace parks as transboundary protected areas that are designated for the promotion of conservation and peace, noting that the value of the PBDI is to showcase their benefits for conservation and conflict. Yunseok Choi, Republic of Korea, lauded the partnership between his government and the CBD in launching the PBDI.

Thanduxolo Joel Mkefe, South Africa, spoke on peace and biodiversity in achieving landscape-level conservation in southern Africa, highlighting that South Africa is moving away from the biodiversity preservation model, which was a tool of exclusion, and toward biodiversity conservation models, which includes local communities managing conservation areas. He drew attention to the removal of people from protected areas during the apartheid era, and the transition from these practices to the opening of trans-frontier parks, which can enhance the protection of shared ecosystem services, as well as contribute to reuniting divided cultures.

Lina Barrera, Conservation International (CI), described her organization’s mission, which includes environmental peacebuilding, and highlighted a conflict root cause analysis in Colombia, noting: definitional issues regarding what conflict is; a need for an overarching mining law; and a need for stakeholder mapping. Drawing from a peace park between Peru and Ecuador (Cordillera del Condor), she noted their contribution to peace and conservation in the area, and highlighted management tools, including meetings with and between indigenous peoples in order to ensure local ownership. Underscoring that men and women access natural resource benefits differently, she noted that vulnerability of women in conflict or post-conflict zones, and discussed CI’s work in Timor Leste in the management of marine protected areas (MPAs).

Trevor Sandwith, IUCN, noted that transboundary conservation may pose a challenge in the achievement of mutual benefits. He said that a transboundary conservation programme could cause socio-economic challenges if management practices are not equally implemented across borders. He underscored that the success of transboundary parks requires cooperation at all levels of authority, describing Austria’s commitment to dealing with migrants through involving them in the management of protected area parks.

Braulio Ferrera de Souza Dias, Executive Secretary, CBD, lauded the Republic of Korea for launching the PBDI at the CBD’s twelfth meeting of the Conference of the Parties (CBD COP 12), as well as the IUCN manual on transboundary conservation. He noted that at COP 12, there were discussions on the demilitarized zone, noting that this is an opportunity for transboundary conservation facilitating peace for the two countries. He stressed the need to share the outcomes on peace building through conservation with the World Conservation Congress as well as the World Parks Congress, and expressed pride in the launch of the PBDI website.

(L-R): Sarat Babu Gidda, CBD Secretariat; Lina Barrera, CI; and Thanduxolo Joel Mkefe, South Africa

(L-R): Braulio Ferrera de Souza Dias, Executive Secretary, CBD; Yunseok Choi, Republic of Korea; and Trevor Sandwith, IUCN

Highlighting work in Liberia’s East Nimba Nature Reserve, Lina Barrera, CI, pointed to work with mining groups and local communities to create conservation agreements, which also promote peace and cooperation.

Trevor Sandwith, IUCN, highlighted IUCN’s publications on transboundary protected areas, and shared that the organization is committed to the PBDI to advance conservation, development and peace.

Drawing attention to his country’s six trans-frontier peace parks, Thanduxolo Joel Mkefe, South Africa, noted the need for the peace parks to be a “homegrown solution,” and called for intentional approaches, transparency and science-based approaches.

A slide from Thanduxolo Joel Mkefe’s presentation.

Yunseok Choi, Republic of Korea

Sarat Babu Gidda, CBD, noted the need for partnerships to strengthen the PBDI.

Participants listen to panelists.

Contact:

- Sarat Babu Gidda (Coordinator)

| sarat.gidda@cbd.int

More Information:

Assessing Equity in Protected Area Conservation

Presented by the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), IUCN and Forest Peoples Programme (FPP)

This event, moderated by Dilys Roe, IIED, discussed the equitable management of protected areas with a specific focus on how equity is defined in practice in terms of the recognition, procedural and distributional aspects.

Noting the history of “top-down” management of conservation areas, Braulio Ferrera de Souza Dias, Executive Secretary, CBD, said that protected area management can be made more effective with the knowledge, experience and participation of indigenous peoples and local communities. He stressed however that equitable arrangements cannot be viewed as a “panacea” and that “we have to be critical to assess and monitor whether conservation objectives are being delivered.”

Phil Franks, IIED, discussed an equity framework, which considers the recognition and procedural aspects, as well as the distribution of costs and benefits associated with protected area management. He described social and governance assessments for protected areas and provided an example of their application in the South Luangwa National Park in Zambia.

Aggrey Rwetsiba, Uganda Wildlife Authority, described how the equitable governance and management of protected areas is key to achieving conservation goals in his country. He stressed that the equity framework adopted by the Uganda Wildlife Authority promotes the effective participation of actors, the acknowledgement of peoples’ rights, values and priorities for wildlife conservation, particularly those faced with human-wildlife conflicts, and the fair distribution of benefits.

Alexandra Rasoamanana, p4ges (Payments 4 Global Ecosystem Services) project, presented on the Ankeniheny-Zahamena (CAZ) protected area in her country and described: the global and local benefits provided by the area; costs borne by local communities from the protected area; the manner by which households were selected for compensation; and the extent to which compensation covers the opportunity costs of households. She lamented that less than 25% of potentially eligible households had received compensation.

Vatosoa Rakotondrazafy, Madagascar Locally Managed Marine Area Network (MIHARI), Madagascar, presented on the state of local marine management areas (LMMAs) in Madagascar. She noted that while there is a high participation of local actors in LMMAs and good recognition of customary governance and management, LMMAs lack the legal framework to recognize the rights and responsibilities of coastal communities.

In the ensuing discussion, participants identified, inter alia: the role of equity in private protected areas; mechanisms to prevent elite capture of resources by either communities or governments; who decides how community-based conservation takes place; whether communities themselves can lead social and governance assessments of protected area management; and reconciling local and scientific knowledge.

Dilys Roe, IIED, moderated the event and noted that social safeguards do not necessarily lead to equitable management of protected areas when procedural equity and recognition of local interests are not considered

Braulio Ferrera de Souza Dias, Executive Secretary, CBD, said equitable protected area management requires respecting the rights of different stakeholders especially those who have traditionally managed these areas.

A slide from the presentation of Aggrey Rwetsiba

Aggrey Rwetsiba, Uganda Wildlife Authority, said that an enabling policy framework has helped to advance an integrated equity framework for wildlife conservation in Uganda.

A slide from the presentation of Phil Franks

Phil Franks, IIED, distinguished between the concepts of inclusion, equity and justice in terms of protected area management.

Participants listen to the address of Braulio Ferrera de Souza Dias

Contact:

- Dilys Roe (Coordinator)

| dilys.roe@iied.org

More Information:

Synthetic Biology and Synbiodiversity: How New Biotechnologies are Raising New Philosophical Questions for Biodiversity Conservation

Presented by Genøk Centre for Biosafety

This event engaged participants in a discussion about the conservation value of the diverse “techno-life forms” being generated through genetic engineering and synthetic biology.

Fern Wickson, Genøk Centre for Biosafety, presented on the BiodiverSEEDy project, which works on different models of in situ and ex situ conservation of agricultural biodiversity, including research on the Svalbard Global Seed Vault and how it should relate to genetically modified organisms (GMOs).

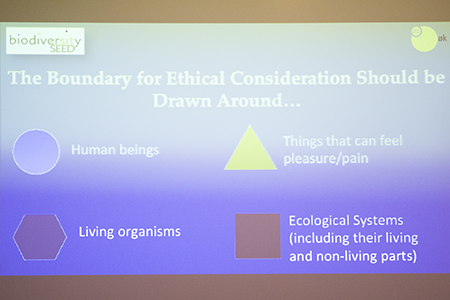

In an interactive discussion, participants then considered the following issues: what is the primary reason to conserve biodiversity; whether human beings can create biological diversity; whether agricultural crop biodiversity is as important to conserve as “wild” biodiversity; whether genetic engineering and synthetic biology increase biological diversity; whether humans can “invent” living organisms; where to draw the boundary of ethical consideration; whether organisms and species have “integrity” value; whether synthetic biodiversity has conservation value; whether GMOs have intrinsic value; and how to evaluate the concept of synthetic biodiversity.

In their responses, participants highlighted, inter alia: that humanity has been creating biological diversity since the beginning of agriculture; the word “create” implies “creating something from nothing,” which is not the case in agriculture; the divide between wild and agricultural biodiversity is artificial as the two interact; wild biodiversity requires increased attention; the importance of agricultural biodiversity for survival; and the danger of corporations narrowing crop diversity.

Members of the audience also commented that: genetic engineering and synthetic biology increase biological diversity since they create new species; GMOs eliminate, rather than increase, biodiversity over time, and it is not just about “surviving in the wild, but also in the market place.” They underlined that xenobiology may lead to the development of something “genuinely novel,” and that GMOs are human made, which “per definition is not natural, and therefore not biological diversity.”

Participants furthermore highlighted that: intellectual property rights recognize that living organisms can be human inventions, but that this may not be appropriate given genetic resources should be considered “common heritage”; species have integrity value given this has been preceded by millions of years of evolution; bacteria or viruses may not have such integrity value; and it is necessary to consider the social, political and economic context in which species interventions are made, and the type and speed of such interventions.

Other interventions suggested that: some types of GMOs, such as animals, have intrinsic value, while others do not; we do not know our future needs, which is why the Svalbard Global Seed Vault should conserve synthetic biodiversity; synthetic biodiversity negatively affects conservation; synthetic biodiversity can enhance the genetic variability of wild populations; the concept of synthetic biology has captured peoples’ attention, which is important for both proponents and opponents in accessing funds; synthetic biology disrupts livelihoods and ecological chains; and having a separate concept for synthetic biodiversity “enables conversations around it.”

In closing, Wickson invited contributions to BiodiverSEEDy’s patchwork quilt project to reconnect the seeds frozen in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault with their history, context and culture.

Participants engaged in a "four corners" discussion, presenting their positions on different statements related to genetic engineering and synthetic biodiversity.

Contact:

- Fern Wickson (Coordinator)

| fern.wickson@genok.no

More Information:

Biodiversity Governance – Identifying Knowledge Gaps and Needed Research Activities

Presented by the Thompson Rivers University and the BENELEX project at the Strathclyde Centre for Environmental Law and Governance (SCELG), Strathclyde University

This event, moderated by Nicole Schabus, Thompson Rivers University, discussed transforming biodiversity governance for a post-2020 strategy for biodiversity in relation to the intersection of diverse legal systems, including on biodiversity, international human rights and indigenous governance.

Marcel Kok, Convener of the Rethinking Biodiversity Governance Network, invited academics, particularly from the Global South, to join the Network, which will consider the Convention on Biological Diversity’s (CBD) post-2020 strategy.

Ingrid Visseren-Hamakers, George Mason University, discussed aspects of the Paris Agreement on climate change that might be useful for a post-2020 strategy for biodiversity. She noted the need to think in terms of process rather than only targets, and to consider appropriate “policy mixes” necessary for transformative change.

Highlighting several “contact points” between international biodiversity law and international human rights law, Elisa Morgera, SCELG, shared findings from the BENELEX project that suggest that human rights standards can provide specific standards for understanding when benefit sharing is fair and equitable, and that international biodiversity law provides specific guidelines on how to put human rights precepts into practice.

Schabus discussed the implementation of indigenous governance around the Fraser River Watershed of British Columbia, Canada. She noted that, as a result of a rollback of federal environmental regulation in Canada, there has been an increasing intersection of indigenous and mainstream Canadian law in federal and provincial courts. She stressed that more research is needed on territorial governance of indigenous peoples, including through their own assessment processes and laws, and on how international standards, including under the CBD and international human rights law, can support indigenous governance of territories, lands and resources.

Arthur Manuel, Secwepemc Nation, predicted the “next big fight” after protesting the Standing Rock Dakota Access Pipeline in the US would be stopping the Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain pipeline in Canada. Noting that “we have been fighting this fight since Christopher Columbus,” he highlighted the need for academic involvement to develop a “workable relationship” between the indigenous, land-based conception of the law, and the “corporate and Eurocentric” vision that holds land as merely a resource.

In the ensuing discussion, participants raised, inter alia: how non-linear interconnections between biodiversity, human rights and indigenous governance can be better integrated for transformational change; the multilevel character of the Rethinking Biodiversity Governance Network; and the role of ecosystem services and their valuation in the framing of biodiversity governance, in light of views inspired by indigenous peoples.

(L-R): Arthur Manuel, Secwepemc Nation; Nicole Schabus, Thompson Rivers University; Elisa Morgera, SCELG; Ingrid Visseren-Hamakers, George Mason University; and Marcel Kok, Convener of the Rethinking Biodiversity Governance Network

Ingrid Visseren-Hamakers, George Mason University, noted that a critical reflection on theories of transformative change is required for a post-2020 strategic plan on biodiversity.

Elisa Morgera, SCELG, stressed the importance of understanding benefit sharing across different worldviews, noting this could help in determining the circumstances under which to withold free, prior and informed consent (FPIC).

Nicole Schabus, Thompson Rivers University, underscored that indigenous governance is “among the strongest examples of biodiversity governance that exists,” noting that traditional knowledge under indigenous peoples’ control is likely the best starting point for rethinking biodiversity governance.

Arthur Manuel, Secwepemc Nation, underscored: “when we talk about protecting this planet in relation to Mother Earth, we mean it.”

Participants during the discussion.

Participants during the event.

Contact:

More Information:

Sharks, Parks and Whales: Non-Extractive Uses of Marine Biodiversity Need Protection!

Presented by Saving our Sharks, Divers for Sharks (D4S), Rede Nacional Pro Unidades de Conservação (RedePROUC) and Manta Ray Bay Resort and Yap Divers

This event, moderated by José Palazzo, Manta Ray Bay Resort and Yap Divers, discussed the values of non-extractive uses of marine biodiversity, such as recreational diving and ecotourism in generating benefit sharing, income for coastal communities and conservation of ecosystems.

Palazzo said the reputation of ecotourism has been tainted by rhetoric of negative effects on livelihoods and ecosystems. However, he noted that the opposite is actually true, and that funds from ecotourism are in practice being used to support the maintenance of ecosystems. He said more research is required to prove the exact impact of ecotourism activities versus the benefits.

Luis Lombardo Cifuentes, Saving our Sharks A.C., spoke on community management of bull sharks in Playa del Carmen in Mexico. He noted that approximately 30 bull sharks come to the area annually and stay for 2-3 months during their gestation, highlighting that Playa del Carmen is not a protected area. He noted the expansion of diving in the area, from one diver swimming with the sharks to over 30 dive shops, all initially operating without understanding the risks involved. He also highlighted the creation of a sharks guide, which had earlier been tagged for monitoring purposes, and underscored the importance of information sharing, education, collaborative participation and public outreach to promote conservation, as well as showcase the non-extractive uses of these sharks.

Angela Kuczach, Redeprouc, said large-scale extractive industries, such as fishing, oil extraction and mining, are unsustainable compared to the economic and conservation benefits that can be accrued from marine protected areas (MPAs) in the long-term. She noted that Brazil after 13 years of no action in this area has, in 2016, enacted a new executive decree for MPA creation, citing campaigns by her organization to encourage more action.

Paulo Guilherme Pingüim, D4S, stressed that everyone knows the oceans are dying, but posed the question of what the people can actually do to address this. He expressed his frustration that the international-level discussions hardly ever represent action on the ground, and underlined that, as this is the only planet we have, we must act now to deal with ocean life. He underscored that we cannot “dump” planet Earth, reminding participants that the Earth is mostly comprised of oceans and seas, and stressed that we should treat the planet as the “mother she is to us.”

Palazzo and Kuczach presented Ugo Vercillo, Director, Ministerio Do Méio Ambiente, Brazil, with two documents: a declaration from the dive industry on the importance of living sharks and rays to generate jobs and income in coastal communities; and the South Pacific Regional Environment Programme’s initiatives on Marine Ecotourism.

Participants then watched a video on people and whales by the Brazilian Humpback Whale Institute, capturing the impressions of first-time whale watchers.

In a discussion, participants: requested information on how to support Saving our Sharks; appreciated the discussions on non-extractive use of marine biodiversity; and called for information on more research boats in Brazil to monitor humpback whales. They also sought clarification on the recovered humpback whale population, with discussions on: the need to address whale deaths due to fishnet entanglement; and whether the government of Brazil was involved in humpback whale conservation efforts. Palazzo noted that the conservation efforts showcased were all financed by the private sector.

(L-R): Paulo Guilherme Pingüim, D4S; Luis Lombardo Cifuentes, Saving our Sharks A.C.; Angela Kuczach, Redeprouc; and José Palazzo, Manta Ray Bay Resort and Yap Divers

Paulo Guilherme Pingüim, D4S, stressed the importance of urgent action to protect ocean life and ensure that future generations can enjoy it.

José Palazzo, Manta Ray Bay Resort and Yap Divers, said that whereas we must recognize and manage the actual impacts of tourism on the environment, non-extractive uses that damage the environment should not be classified as ecotourism, and lamented the lack of fora for inputs from non-extractive businesses into international processes.

Angela Kuczach, Redeprouc, said Brazil has an important opportunity to achieve Aichi Biodiversity Target 11 on protected areas.

Luis Lombardo Cifuentes, Saving our Sharks A.C., outlined that the Saving our Sharks project now has over two million allies, with more than 41 participating dive shops, and more that 80 shark-free tourist resort sites worldwide.

Participants listen to the address by Luis Lombardo Cifuentes

Contact:

- José Palazzo

| palazzo@mantaray.com - Angela Kuczach

| angela@redeprouc.org.br