Voices from the Field: Participatory Approaches of Climate Smart Agriculture Practices, Farmer Field Schools and Indigenous Chakra Systems

Community-based approaches are crucial to finding concrete, adapted, and sustainable solutions to climate change in the agriculture sector as they integrate scientific insights into local knowledge systems, empowering local actors to take the lead in improving their production systems.

This event highlighted the potential of community-based, bottom-up strategies in agriculture to implement and scale up climate change commitments, showcasing Farmer Field Schools (FFS), climate-smart agriculture (CSA), and Indigenous Chakra systems. It was organized by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN (FAO) and showcased practical on-the-ground experiences followed by a discussion of their potential.

The discussion highlighted:

- the potential merits of an agroecological approach to CSA compared to other forms of CSA that may include soil-degrading chemicals;

- the need to integrate science and traditional knowledge and how best to do this; and

- best practices in the implementation of sustainable agriculture on the ground.

Liva Kaugure, FAO, moderated this event.

Ceris Jones, UK National Farmers Union, said 3.4 billion people, including small farmers, live in rural areas that are most vulnerable to climate change. Saying farmers learn best from other farmers, she recommended bottom-up approaches that bring science and local knowledge together, as well as designing development policies and investment strategies that give rural people tools for scalable, locally adaptable approaches.

Petan Hamazakaza, Zambia Agriculture Research Institute, said his institute develops technologies for different agricultural regions and socio-economic and climatic circumstances. He noted potential solutions are being developed through farmer-to-farmer information sharing on different varieties of plants, such as for early maturing or tolerance to drought, disease, or pests, to build resilience and decision making capacity to address different climate risks.

Eularia Zulu, Farmer and Chair, Chongwe District Agribusiness Hub, Zambia, reported on Save and Grow FFS training in conservation agriculture based on mechanized direct seeding (no tillage), crop diversification, and intensification of the frequency of the crops in rotation. She noted benefits include labor-reducing and yield-increasing sustainable mechanization.

Alimatou Badji, Association for the Promotion of Senegalese Woman, said problems that are increasing due to climate change include decreasing rainfall and increasing crop-damaging pests and diseases. She reported that FFSs incorporating agroecology and reforestation have improved resilience, yields, food security, and financial independence for women. She said her group chose not to use chemical inputs but that governments must subsidize organic agriculture to enable farmers to use it.

Lamine Diatta, Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development, Senegal, said the government tries many approaches at the strategic level but the still-pending question is which of them is most effective on the ground. He said one very successful approach trains “champion” farmers who deliver know-how to other farmers who then begin implementing those approaches as well. He said contextual differences, climate change impacts, and effective practices must be understood, to build “no-regret” actions on the ground that feed into climate policies.

Participants then viewed a video on cocoa production in Ecuador. Geovanny Enriquez, FAO Ecuador, elucidated further, saying Amazonian Kichwa farmers, particularly women, have created a Chakra label for their cocoa agroforestry that increases resilience of the forest and provides other food and medicinal products. He said elements include adaptation to climate change through diversification, a focus on niche markets for best quality cocoa, and access to carbon offsets. He said public policies must support the adoption of good production methods.

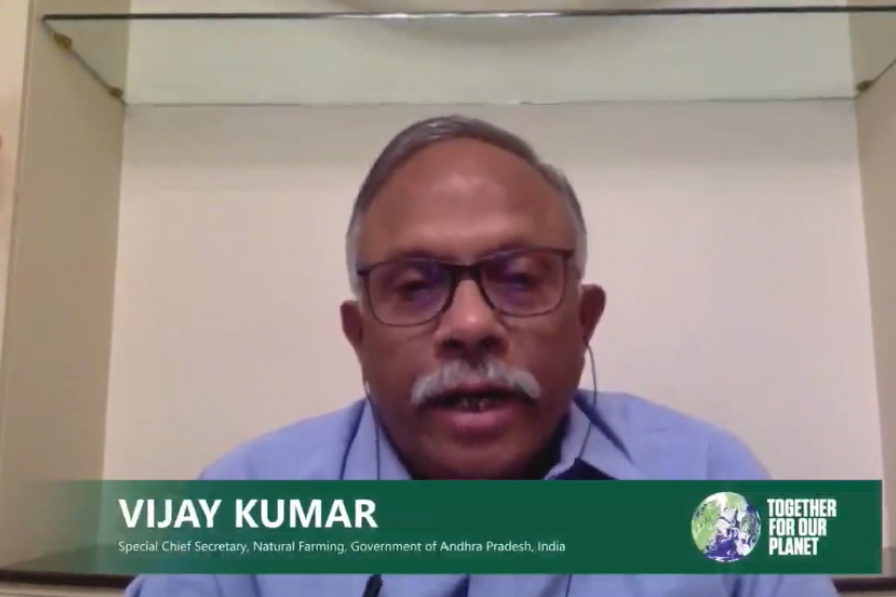

Participants also watched a video on agroecology and FFS in Andhra Predash, India. This was followed by Vijay Kumar, Government of Andhra Pradesh, presenting on an agroecological transition for all six million farmers in the region using existing self-help collectives that also address social issues. He said: farmers have been told for 50 years that crops cannot grow without synthetic materials; everyone must cooperate to achieve the required change, including civil society and farmer champions; and governments and institutions must check theories against on-the-ground reality.

Karl Deering, CARE USA, reported on CARE’s Farmers Field and Business Schools (FFBS) in Tanzania, based on the FFS model. He said the FFBS curriculum incorporates: context-specific production; nutritional information; empowerment in men’s and women’s competencies to bargain, engage in markets, and demand rights and services; and participatory monitoring and evaluation. He said equitable gender behaviors are addressed through engagement with men and boys, which also mitigates gender-based violence. He cited substantial evidence that the FFBS and similar models work well and bring a variety of benefits.

In the ensuing discussion, questions focused on: potential differences in outcomes and the sustainability of agroecology and CSA; scaling up knowledge from Andhra Pradesh; and chemical fertilizers’ degradation of soils. One participant called for more emphasis on traditional knowledge in policymaking.

Panelist responses focused on:

- national agriculture policy in Senegal currently incorporating agroecology to test its effectiveness;

- the importance of farmers’ and indigenous know-how and placing learning and decision making in farmers’ hands;

- “the myth” that soil-degrading synthetic fertilizers are needed for higher yields;

- the need for evidence-based technical and participatory interventions to make CSA sustainable, including research, extension, and FFS;

- the need to recognize that some CSA represents improvements over traditional methods and a holistic approach requires connecting all angles, including research, FFSs, and CSA; and

- linking CSA and sustainable agriculture practices, which requires farmers’ participation, local government support, and strong national policies for implementation.

In closing, Martial Bernoux, FAO noted the event had over 130 participants in-person and online. He said behind the different names of approaches is a common theme which the session emphasized: the importance of having the people present who are implementing solutions. He said agroecology has elements that have been approved by FAO as an analytical framework; “these must now be implemented on the ground.”

CONTACT

Awa Mbodj | Awa.Mbodj@fao.org

MORE INFORMATION

Strengthening Agricultural Adaptation (SAGA) Global Project

To receive free coverage of global environmental events delivered to your inbox, subscribe to the ENB Update newsletter.